Advice to a Young Physicist

As several people have recently asked me for thoughts and advice regarding their tender offspring who have an interest in physics and are thinking of going into it full-blast, I thought I would gather my scraps of wisdom on this subject into one place. Below are a few random items that I sincerely think would be good, at least, to think about, for the student in high school or college who wants to be a physicist.

This is a work in progress. Please comment using the link at the bottom to suggest more advice, or books or articles that I should link to.

- Learn some oddball mathematics. Take a course or two over in the math department that is not standard for physics majors (this advice applies mostly to undergraduate school). Probability theory, graph theory, it doesn’t matter. Pick a course taught by a professor whose teaching you like. This will be fun, give you a different perspective, and might wind up suddenly useful during your research career.

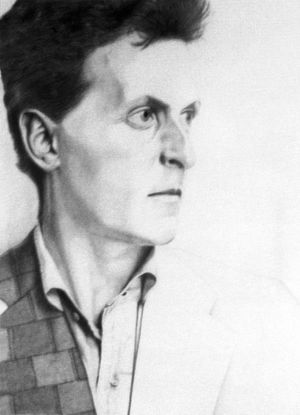

Don’t expect to get a job actually doing physics. The prospects for this are not excellent. This might be an advantage if you love physics, as spending time writing grant applications and squabbling over resources tends to spoil the fun. Wittgenstein, one of the most important philosophers of the 20th century, advised his students to go into farming or something useful, and do philosophy as a hobby. This advice does not apply if you want to work on large experimental projects, the space program, etc.

If you do get a job, especially outside academia, brace yourself. You might get lucky — I’ve worked in groups with vastly differing personalities, within the same large government laboratory. The chances are great that you will encounter plagiarism, cheating, and credit-stealing on the part of senior staff. This is all considered normal and routine in many institutions. Your bosses won’t care about correctness, or honesty, or physics, but mainly about raising money to support their departments. If you find yourself in such a group, don’t waste your time trying to reform it. Just look for a better group. Or, see (2).

Learn how to use a computer. This means learning Linux, becoming expert in the command line, and using version control for everything. This applies even if you’re not interested in computational physics, because you will use your computer for writing papers, making diagrams, organizing literature, etc.

Study as many different areas of physics as you can. One of the beautiful things about this subject is how everything is connected — how the same ideas and techniques crop up in widely different places. Try to avoid prejudice against certain topics: when you see them for the first time it’s too early to decide that they’re boring or useless.

Study classical mechanics deeply, especially its variational formulations. Not only is this an elegant and beautiful subject, but all of modern theory is based on it.

Make sure you learn something about fluid dynamics (and maybe elasticity and other areas of continuum mechanics). If this is not normally covered in your department, try to find time to study it on your own. Not only is this interesting, but it’s great preparation for research in many fields. Also, you might understand why airplanes fly, which gives you a leg up over most physicists.

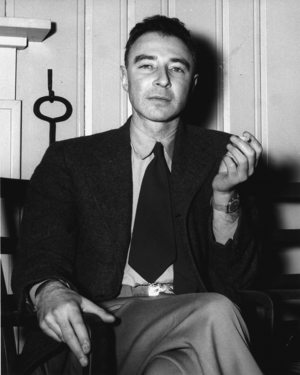

Most of your supervisors and bosses will know more than you, but not always. Try not to be shocked. Remember, the most famous physics boss in the history of physics bosses, J. Robert Oppenheimer, was a big phoney.

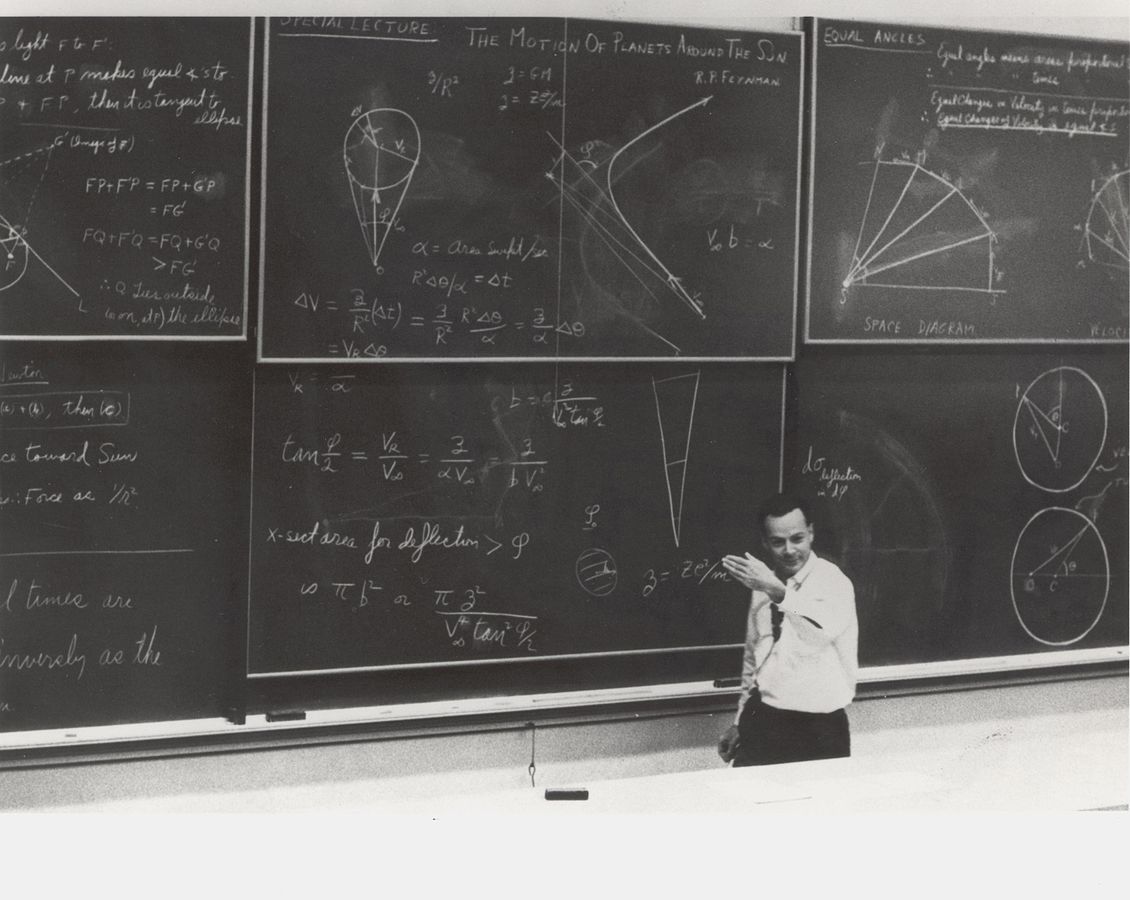

Suggested reading: Advice to a Young Scientist; The Feynman Lectures on Physics; advice from John Baez.

Oh no, I’m not Feynman! Imposter syndrome can strike anyone, anytime. Avoid comparing yourself to the greats of the past, or the know-it-alls in your building. When you’ve been on the project as long as they have, you’ll speak the jargon of your subfield as fluently — but you may want to change jobs before that happens to you. If you’ve followed the advice in (1) and (7), you might find that you have a personal take on a problem that would not occur to others, despite their superior knowledge or even ability.

Try to remember that physics is not a profession. The professions are fields such as medicine and engineering, where (thankfully) there are official barriers to entry. A physicist is someone with a pencil and paper who does physics. Some of them don’t have physics jobs (see (2)), and plenty of people with physics jobs haven’t done physics in years.

Physics may superficially resemble engineering, because the languages they speak have a large intersection (differential equations, trigonometry, “force,” “current,” etc.), but physics has more in common with poetry than with engineering.